This is an edited extract from Priyanka Kumar’s book The Light Between Apple Trees: Rediscovering the Wild Through a Beloved American Fruit, published by Island Press in September 2025.

Buy a copy by clicking here.

Few of us live on the same land where our grandparents, or even parents, once harvested fruit. The twentieth-century movement of American people from the country to the city, and the relentless urbanisation that ensued, sundered us from the land.

Apple orchards were not exempt from this shift. In the post–World War II era, many were bought out by commercial interests. New, specialised orchards developed a hyperfocus on yields and sugary sweetness, attractive-looking fruit, and varieties that could endure long shipping days.

In the industrial phase of our apple history, the obsession with sweet fruit and supermarket-ready skin spurred a modern reshaping of fruit, stoked by greed and sanctioned by government. A 1959 government guide to apple production actually coached growers that “sales may be increased 75% on the average by increasing the area of solid red color from 15 to 50%.”

Americans got hooked on colour. A ranger at the Los Luceros Historic Site in New Mexico told me that after seeing the big, red apples in The Wizard of Oz (1939), many Americans began to grow the Red Delicious apple. For me, the apple’s “lipstick red” colour signals the loss of genetic diversity in commercial varieties and how during the industrial makeover, the soul of the apple and its marvellous complexity got lost.

When I visited an orchard in Chimayo, New Mexico, Golden Delicious trees towered over us, teeming with shade and character. It is unusual to see such a generous canopy on a modern apple tree. Under the influence of the US Department of Agriculture, fruit trees weren’t allowed to grow to a mature height of five feet or taller, and natural tree shapes were discouraged. The exclusive focus on commercial fitness and high yields inevitably led to the varieties being grown plummeting – from many hundreds to tens.

The aggressive mass production of fruits after World War II sounded a death gong for a plethora of fascinating apple varieties. Commercial growers pumped the soil with unprecedented amounts of pesticides and fertilisers to stimulate ever higher yields. Their strategies did work in the short term, but decades later, we are realising that conventional fruits and vegetables are grown at terrible costs to the earth and us. Americans now collectively use a billion pounds of pesticides and 50 billion pounds of fertilisers each year. Pumping artificial chemicals overstimulates the soil and ultimately deadens it.

Just as the fairy tale Snow White almost chokes on a poisoned apple, our real-life apples are now laced with toxic chemicals. American apples are sprayed routinely with diphenylamine, a chemical treatment that prevents their skin from developing brown or black patches (known as storage scald) while in cold storage. Because of their high pesticide residues, apples appear near the top of the Environmental Working Group’s list of “Dirty Dozen” fruits and vegetables.

Diphenylamine is banned in the EU, but American farmers continue to apply it liberally. European officials have concluded that diphenylamine can combine with nitrogen-containing compounds to form nitrosamines – a category of chemicals that includes “strong carcinogens”. Studies have found links between people who eat foods with nitrosamines and elevated rates of stomach and esophageal cancers.

Near industrial orchards and farms where artificial fertilisers are used, phosphates from the fertilisers wash into rivers and then into the sea, leading to algae blooms and dead zones. Nitrate, mainly from polluted farm runoff, contaminates the water supplies of some 1,700 communities nationwide at levels the National Cancer Institute says could increase the risk of cancer. Among crops most doused with pesticides are cotton and apples.

Over the last century, conventional orchards have become a monoculture of lookalike trees in unrelenting rows. The apple itself has gone from being a highly acidic fruit, prized for cider and dessert, to a cloyingly sweet supermarket staple.

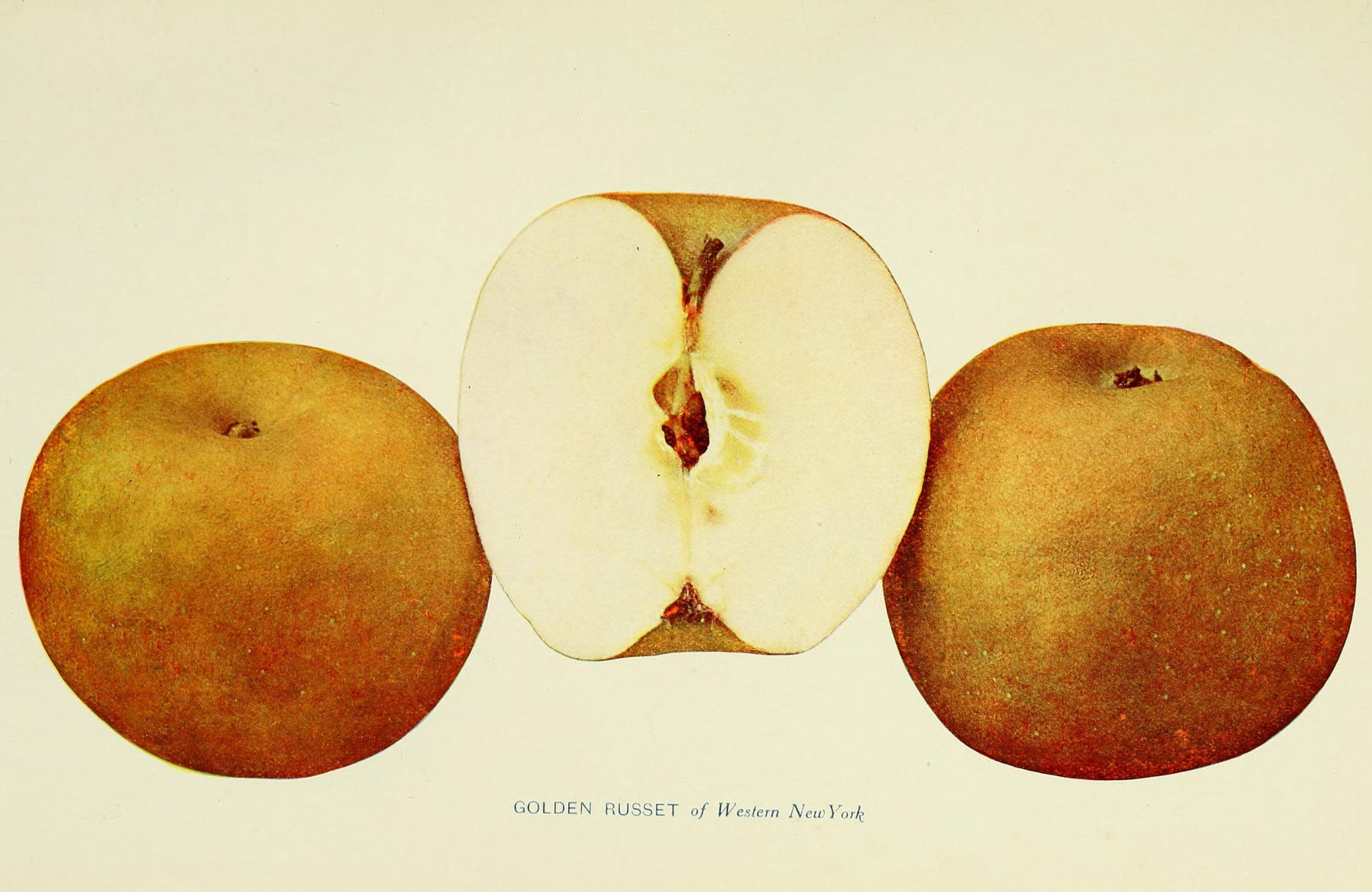

We have also lost our rich apple lore. Who knows anymore that the antique New Yorker, the Golden Russet (seedling of the English Russet), is the champagne of cider apples or that the relatively modern Winecrisp is excellent for pickling? That the Northern Spy needs to go into cold storage for a couple of months before its flavours develop fully, and the Wickson boosts pollen for cross-pollination?

The loss of experiential knowledge – and an overreliance on pesticides – has repercussions for the rest of the ecosystem. 5% of commercial orchards should be pollinator plants such as the Wickson. Scientists have observed that large apple orchards in China have lost their natural pollinators, most likely due to an excessive use of pesticides, and now rely on migrant workers to hand pollinate apple blossoms.

Early successes with apple growing were co-opted by agribusinesses, and the varieties Americans once celebrated are scarcely known today. Now our challenge is to circle back and think wild, to wander back to orchards that will nourish us instead of fattening corporations.

‘The Light Between Apple Trees’ was published by Island Press in September 2025. Purchase a copy here.

Priyanka Kumar is a naturalist and writer, and the author of 2023’s Conversations with Birds. She has taught at the University of California Santa Cruz and the University of Southern California, and serves on the Advisory Council of the Leopold Writing Program.