This is an edited excerpt from Matthew Hole’s interview on The Land and Climate Podcast. Listen to the full episode below.

Nuclear fusion powers the stars. There is no way for us to reproduce the density and pressure that fuses stellar protons, so earth-bound efforts rely on creating extremely hot conditions: hotter even than the Sun’s core. The aim is to sustain fusion reactions at high enough volumes to produce net power – a very difficult thing to do.

Fusion could deliver a vast amount of energy for our civilisation, without the dangerous waste or risk of chain reactions associated with conventional nuclear fission power. This promise has attracted nearly $10 billion in private investment over the last five years, as companies compete to be the first to demonstrate fusion power. Winning this race could generate unprecedented wealth.

Investment is welcome: it accelerates development, advances new technology and diversifies risk. Some of the accompanying announcements are less welcome, however, and it is important that scientists tell the truth: to say that nuclear fusion will be producing power within five years is ludicrous.

Fusion is not mature technology. It has never been trialled before. It will take at least until the mid-2030s to operate in burning plasma regimes, which is necessary to produce net power.

Many – if not all – of the companies saying otherwise will go bankrupt. Realisation of fusion is a hard challenge, and no amount of corporate ambition can overrule laws of physics and nature.

The biggest danger in misleading claims is not to investors – it is that a private sector collapse wipes out the public sector too. Fusion has long term attraction, but there is a risk of being commercially overcapitalised at an early point in the timeline, which could have knock-on effects to the research sector more broadly. The public sector overpromised during the oil shocks in the late 1970s; if a similar thing were to happen again, it could significantly set back development.

Private investors should accept that the risks inherent with fusion are also why it promises such large returns. Highly speculative investments involve very high gains, but would I bet my house on fusion? Absolutely not.

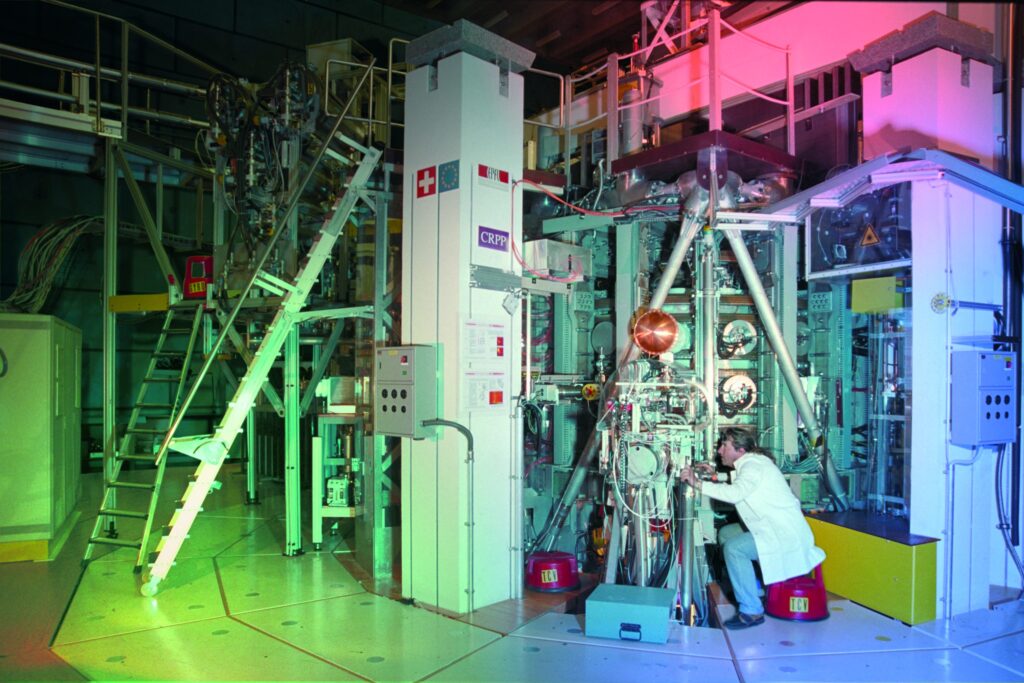

Realistically, the technological demonstration of fusion is not going to occur until the International Thermonuclear Reactor (ITER) mega-project has achieved it. Current plans put that in the late 2030s.

Fusion power plants, for the most part, are gigawatt electric devices. They are large facilities. Even after fusion energy is demonstrated, building power stations of this size would take around 10 years. It is unlikely that fusion will contribute power to the grid at scale before 2050.

ITER was spawned as an agreement between Gorbachev and Reagan – a path forward during the Cold War. With an international foundation, it expanded as a multi-party activity with alliances all over the globe. ITER has faced many challenges, but right now it is not only on track, it is slightly ahead of track, which is unusual. If you were to bet on fusion, ITER is the most likely to win the race to sustained burning plasmas: it is making remarkable progress.

When this happens, ITER will have a strong claim to being the hardest project ever completed by humankind. It should be no surprise that such successes take time – they are worth waiting for.

As told to Bertie Harrison-Broninski, with additional editing by Anna Spree.

Matthew Hole is a professor at the Mathematical Sciences Institute at the Australian National University and a leading authority on plasma fusion physics. In 2005, he founded the Australian ITER Forum and currently serves on the International Fusion Research Council of the International Atomic Energy Agency.